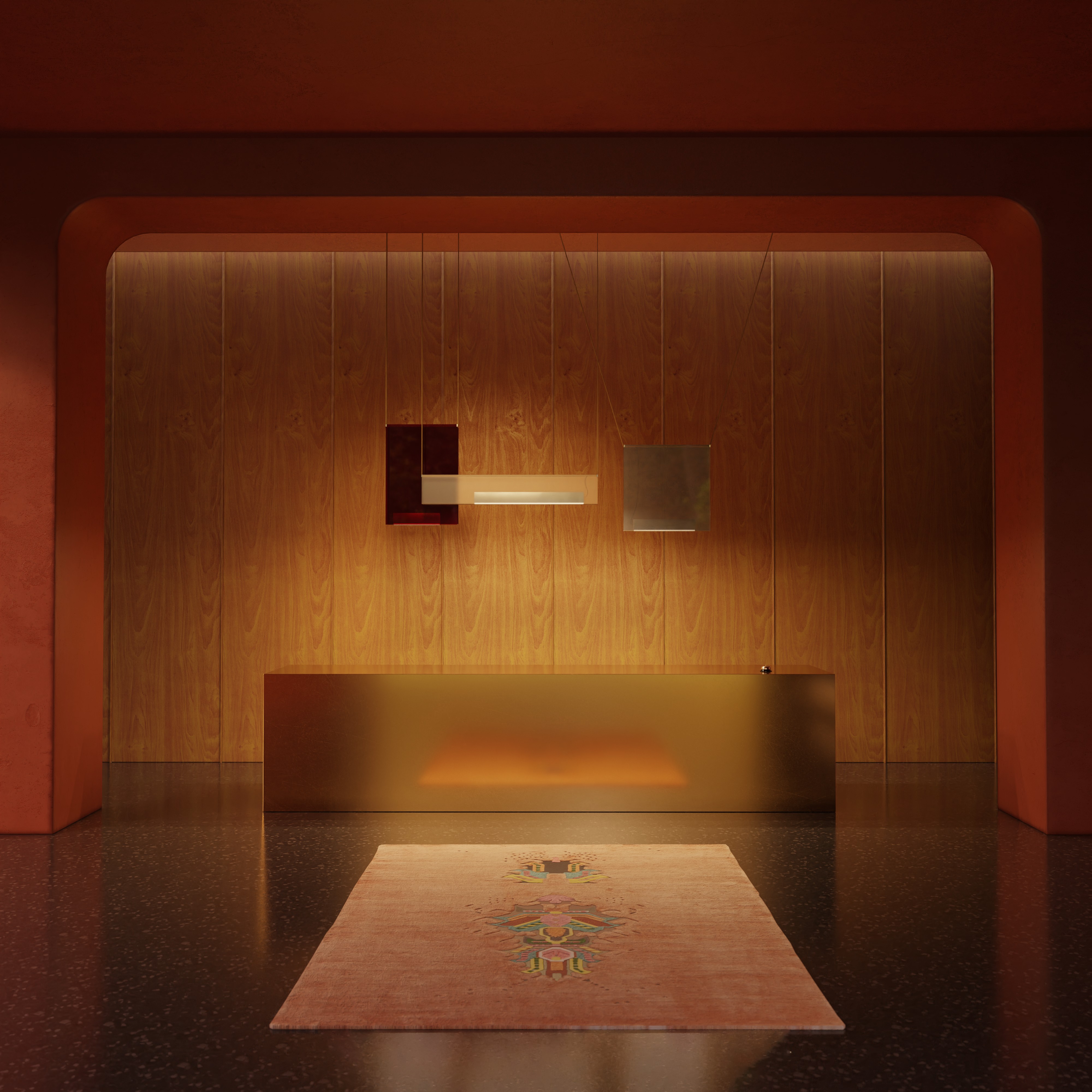

Inspired by the romantic contours emblematic of the Art Nouveau movement, the Beaubien Atelier 06 suspension lamp’s harmonious energy brings a space to life.

For the Love of Craft is a new series on the Hollace Cluny blog which celebrates the passion that drives our creative community forward.

It’s fitting that our first post in this series centres around the vibrant and forward-thinking studio of Lambert & Fils. Since its launch in 2010, this Montreal-based company has retained founder and artistic director Samuel Lambert’s “commitment to the handmade”.

Amplifying what the studio describes as “the poetry of materials – encounters of technology and design”, the alluring offerings from Lambert & Fils range from the melodic silhouettes found in the Beaubien Atelier collection to the energizing array in Sainte Atelier’s assortment, a colourful cache of lighting styles made in collaboration with Canadian designer Rachel Bussin.

Yet it’s not only the lyrical nature of Lambert & Fils’ lighting design that sets this internationally acclaimed studio apart; a commitment to sustainably-minded innovation and community collaboration is also integral to its business.

To mark his studio’s debut on Hollace Cluny’s roster of exceptional makers and designers, Samuel Lambert shares the familial foundation of his unique explorations in lighting design; his favourite projects to date; and how his background in fine art and cinematic studies have inspired his studio’s thoughtful and eclectic contributions to the interiors landscape.

Let’s start by talking about your father and his ceramics practice, and why making things by hand excited you then and still excites you today.

I grew up around my father’s workshop; he was a ceramicist in the 1970s and we lived in the Eastern Townships of Quebec. At this time, the craftsmanship in this area was very interesting and internationally important. Other ceramicists from all regions of the world often visited and bonded with my father around their shared ideas and techniques. The specific village we were in is called North Hatley, which was well known for ceramics in Quebec.

And what then drew you to lighting as a medium? Ceramic art is very earthy, and lighting can be very technical.

My inspiration came from my background in fine art and cinema. The idea behind Lambert et Fils is that we make sculptural forms that create light – they are interesting objects, and their lighting component is secondary.

Since then, we’ve been driven to also create specific types of light, but most of our collections have started with form and materiality first. And when we talk about materiality, we’re getting closer to what my father was doing in his workshop – like when we’re polishing aluminum or adding a patina.

It’s funny because I feel like I just closed the loop on this; I recently finished working with Côté Est, a restaurant in Kamouraska, in Eastern Quebec, where I now spend my summers. I created a collection using ceramics and glass made by local craftspeople, and it was my first time working with ceramics. It was a small-scale project but it has significance for me.

The organically sculptural elegance of waterfalls and weeping willows influenced the design of the Beaubien Atelier collection.

Let’s go back to how your perspective was shaped by cinema and fine art. What about those studies in particular stand out to you as contributing to the work you do with Lambert et Fils?

When I was a film student, most of the films I watched were black and white. It was the time of nouvelle vague – Truffaut and company. And I also watched a lot of Canadian-made documentaries; we have a lot of very talented local cinematographers. So, I’m interested in how someone can play with light; I feel that light itself is a kind of materiality. And I’m also interested in the dialogue between the object which creates light and ambient light, or the sun, and how it influences that object.

Why was it important for the studio to develop its own LED technology? And can you explain what its sustainability component is?

We wanted to develop our own LED technology because we wanted to use the highest quality LED possible, and found the market lacking in that area. Furthermore, by using high-quality LED such as our own technology, we ensure that our lights last longer and also, that they can be repaired, which are two important components of sustainability.

You’ve mentioned materiality a few times. How does the studio’s process account for experimentation? Are there any collections you’ve done that have had an unexpected result?

Well, the Silo collection is a great example of how experimentation leads to creation in our process. We started out by creating the raw material for the project, an extruded shape, and produced it in the largest form available to us (10 inches). Then we played with those shapes, cut them and mixed them to form new ones. The Silo lights (but also the Silo vases, our first foray into a non-lighting object) emerged from those experimentations, but not out of thin air: it always starts and ends with materiality, and the result is quite often unexpected.

A traditional chandelier’s silhouette is given a modern, customized update in the Silo Atelier collection.

What have been some of your favourite collections or projects to work on?

Being in the position of founder and artistic director of the studio, the most recently finished project is always the favourite child. But once it’s completed, it’s the next project – the one in the pipeline – which becomes the favourite. Because once something is finished, it’s no longer ours. It belongs to whomever lives with it.

The Silo collection is important to me because it all came from our studio. We do everything in Montreal – designing, manufacturing, selling. That’s why our team has about 45 people; everything is done internally. And the Silo collection was all done by our team, not with an external collaborator. Our studio collaborated within itself. We have an open-concept 20,000 square foot space and people are encouraged to move freely and give feedback.

And why is collaborating with designers who work outside the Lambert et Fils studio something you believe so strongly in doing?

It’s a way to create a dialogue not only inside our company but to see how our company is seen from the outside. For me, everything is about communication, and when we do a collaboration, it’s because I want someone to question my ideas and have an exchange.

It takes around two-and-a-half years for a collaborative project to go from the initial sketches to bringing it to market; we have to know from the start that it’s right on because we have to live with it for quite a while. And we have to be sure we’ll believe in it after a few years.